One of my devotional practices for Lent has been to meditate on paintings of the life of Christ, particularly the works of three artists: James Tissot, Georges Rouault, and William Kurelek.

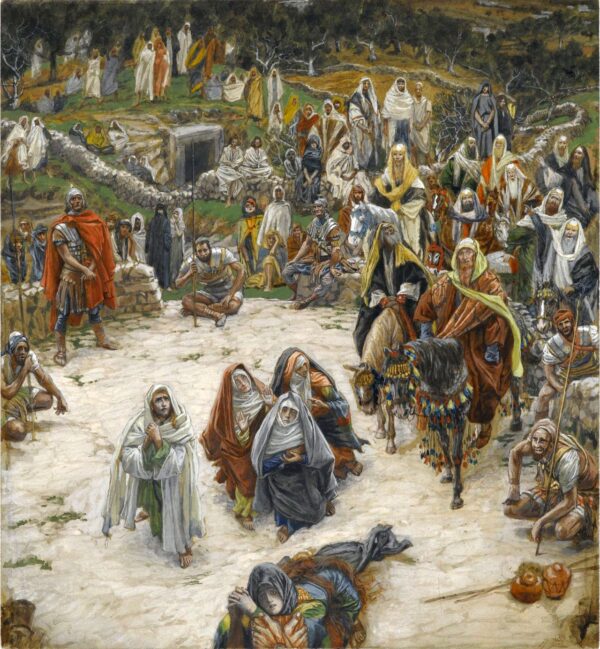

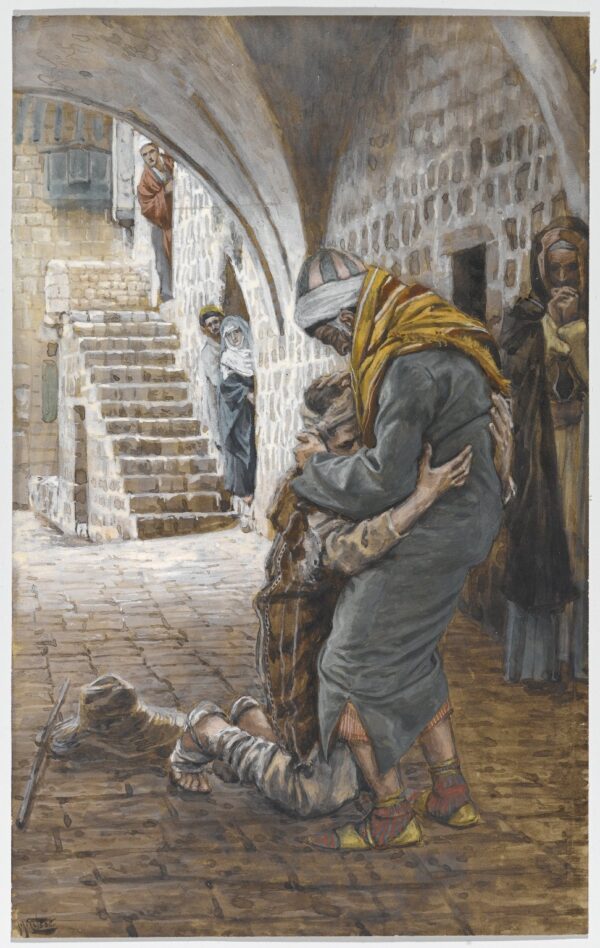

James Tissot was a painter of fashionable genre scenes of upper class English life, who in 1885 experienced a radical conversion to Christ, and thereafter produced only sacred works. He took several trips to the Holy Land where he made endless sketches of the people, buildings, and landscape in order to portray Biblical scenes with scrupulous authenticity. His series of 350 watercolor paintings of the life of Christ is now housed in the Brooklyn Museum.

Over and over in Tissot’s work, what catches my eye is his unusual perspective on familiar gospel stories. In several pictures of the young Christ, the child looks out directly at the viewer with depthless, arresting intimacy. His mother Mary is portrayed as an old woman, gazing down at the small hole in the ground where the cross had once stood. In Tissot’s “Crucifixion, Seen from the Cross,” rather than the crucified Himself we see the crowd before the cross as Jesus would have viewed them. And while I’m familiar with Rembrandt’s rendering of “The Prodigal Son,” that painting has never spoken to me as Tissot’s version does, in which I’m right there: I myself am the prodigal, wrapped in his father’s arms and being embraced by the love of God.

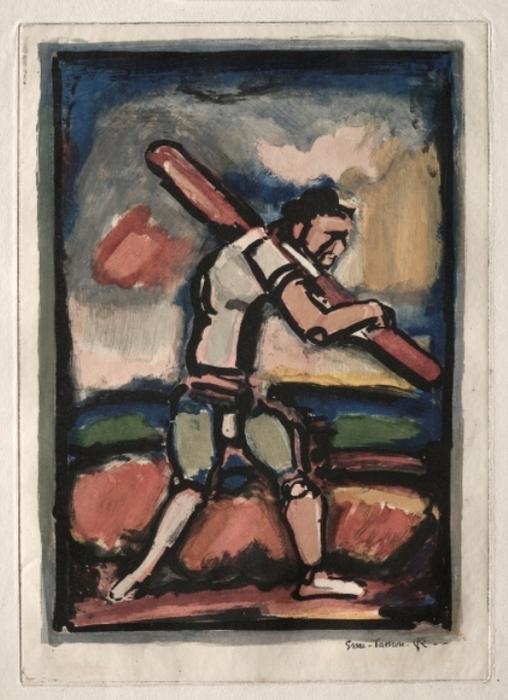

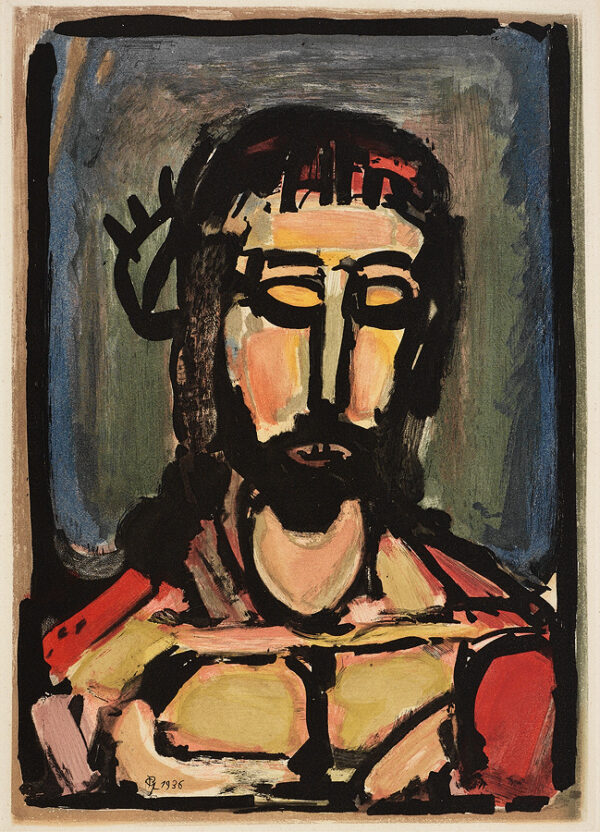

Another modern artist who devoted himself to painting Christ was Georges Rouault, in a series called simply The Passion. Unlike Tissot, Rouault did not depict the Easter story as a set of scenes from the gospels. In fact Jesus Himself appears in only some of his works, while many others show the suffering of ordinary people. There is, for example, a “Blessed Whore,” who may or may not be Mary Magdalene, and a “Man Carrying Wood,” which may or may not be wood for building the Cross. For Rouault saw all human suffering as reflecting, and involved in, the suffering of Christ, and therefore sacred.

Apprenticed to a stained glass maker in early life, Rouault’s mature art continued to retain the bold colors and black outlines of stained glass, no doubt to suggest that these works were suitable to adorn a cathedral. Indeed this was the only major twentieth-century French artist whose work remained predominantly Christian in imagery. Whether the subject was a peasant, a judge, a clown, or a prostitute, every face was the face of Christ. “As a Christian in such hazardous times,” said Rouault, “I believe only in Jesus Christ on the Cross.”

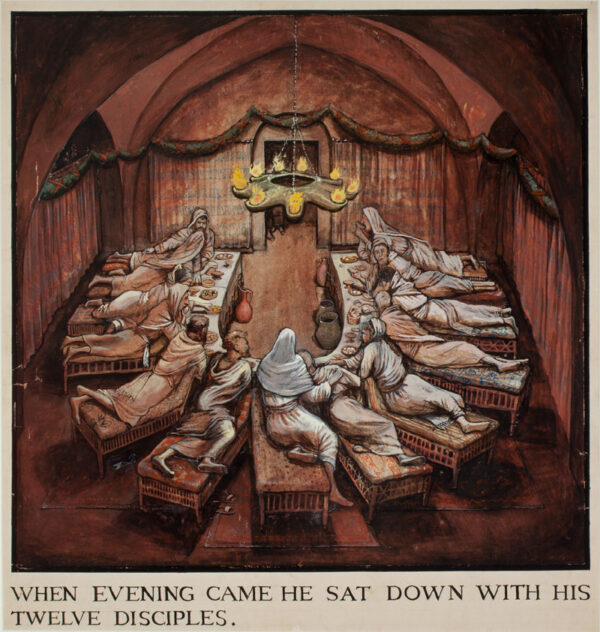

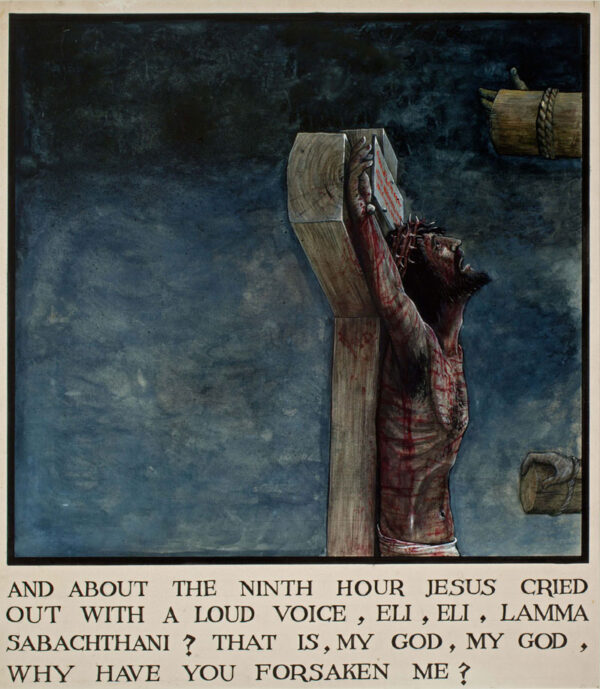

Finally, the third artist I’ve been studying for Lent is the Canadian William Kurelek. His cycle of 150 paintings, called The Passion of Christ, depicts the Easter story verse-by-verse from the gospel of Matthew. Kurelek worked on this series exclusively for six years, a true labor of love. The entire set is now housed in the Niagara Falls Art Galley, where the artist’s workshop, transported from Toronto, is also on display. When I visited, guess what I noticed lying on Kurelek’s workbench? The book The Life of Christ, containing the paintings of James Tissot.

Ukrainian artist Natalka Husar has described her powerful reaction at age twelve upon first seeing Kurelek’s paintings of Christ’s Passion: “It wasn’t just paint, or an illustration of a story we all know, but something he couldn’t not paint—because he had to tell you this story. It was like he went somewhere, and he saw it. And he sent a picture back for you to see. Like he’d seen it with his own eyes.”

And so my journey through Lent this year has been wonderfully illustrated by three amazing artists, all of whose works may be readily viewed online.

To all of my readers — a blessed and holy Easter!

Next Post: Psalm 139: A Nocturnal Prayer