Watch this on YouTube or read the text below.

Of the 150 psalms in the Psalter, only five are penitential prayers, while fifty are laments. The difference between the two is that psalms of penance seek God’s forgiveness through confession and contrition, whereas psalms of lament are merely complaints. The penitent acknowledges sin, beating his breast, but the lamenter knows he has done nothing wrong, nothing to deserve his suffering.

In our churches we often allow room for public confession and repentance, but when are we ever invited to complain? If lament comprises such a large portion of the biblical psalter, why do we neglect it? Why have we no songs and prayers of lament? There are forty days of Lent; might we not set aside even one day for complaining? How about designating the week before Thanksgiving as Complaining Sunday?

I speak tongue-in-cheek, of course. There is an obvious reason for not having a Complaining Sunday, which is that we probably do enough complaining as it is. From the time of Adam, part of our fallen nature is to shirk blame and pass the buck.

However, there is another reason we are not comfortable with enshrining complaint, which is that, beneath all our defensiveness, we never really feel blameless. Whatever trials we may experience, we always know, at some level, that we’re only getting our just deserts. Suffering is the common lot of sinful humanity. The whole world is suffering and why shouldn’t I? While my particular pain or trial may not be directly related to something I’ve done wrong, even so I remain a sinner, and I also hold some share in systemic injustice.

So, no matter what we’re going through, we really have no reason to complain. We don’t have a leg to stand on and we know it.

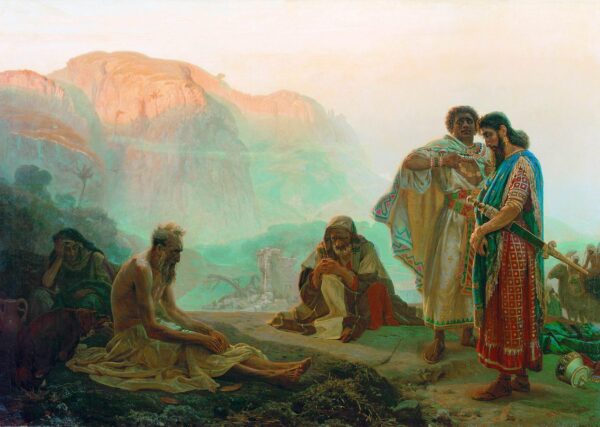

Enter Job, a man whom scripture describes as “blameless,” and who spends a good chunk of a long biblical book complaining.

Our problem is that in our readiness to assume blame, we have no category for blamelessness. We’ve lost sight of the imputed righteousness promised in the gospel of Christ.

This is the central theme of my book The Gospel According to Job. Job is a righteous man, blameless in the eyes of the Lord. True, in the end he repents in dust and ashes, but before that point he gets away with a whole lot of complaining.

Job refuses to accept condemnation from his friends, or even from his own conscience. The only conviction he will listen to is that of the voice of the Lord. And so in my book he is the Old Testament poster boy for the man of faith, the original righteousness-by-faith Christian who intuitively grasps that “there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom 8:1). Having believed in and accepted forgiveness from God, and knowing he is in right relationship with the Lord, he takes his stand on his blamelessness.

This is the good news of the gospel, about which Paul wrote, “In the gospel the righteousness of God is revealed—a righteousness that is by faith from first to last” (Rom 1:17). Or as John the Baptist proclaimed, “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (Jn 1:29).

This doesn’t mean we no longer sin. It means that sin is easily dealt with: We confess it, we repent, and we’re done. Sin can be sent packing on a moment-by-moment basis. Even chronic sin is forgiven chronically. There might be consequences, but we accept them. For this does not mean that we do not suffer—we do—or that the Lord may not discipline us—He does. But we deal with all this from a place of blamelessness, as pure and righteous children of God.

The mission of Jesus Christ was not to eradicate sin—not yet—but rather to lift the burden of sin. For the real prize God is after in our souls is not sinless perfection—not yet—but faith: trust in Him, and love for Him, even in the midst of our sin, weakness, suffering, and all the messes we get ourselves into. Faith means not just believing in God, but in ourselves as redeemed in Christ. And so we live in the truth of one of my favorite book titles: Living Totally Without Guilt.

Among the believer’s weapons of war that Paul lists in Ephesians 6 are “the shield of faith,” “the breastplate of righteousness,” and “the helmet of salvation.” It makes all the difference to fight your battles from a place of being forgiven, cleansed, loved, entirely right and intimate with God. Surely this is what David meant when he sang, “The Lord is my rock, my fortress and my deliverer, my shield, my stronghold, and the horn of my salvation” (Ps 18:2).

This is what I learned from my study of Job over thirty years ago, and it is still what I live by today. Living this way has revolutionized my life.

I still recall clearly how the idea for this book came to me. Though I was already a Christian, it was almost a Damascus road experience, though without the sound and light show. It all came to me in a single flash of insight: how to interpret the story of Job in light of the gospel, and how that message applied to my own situation.

People wonder what sort of ordeal I was facing when I wrote this book. I deliberately withheld that information, in hopes that the book might have relevance for those with much weightier suffering than mine. And so it has. But at this point, it’s no secret what my problem was: it was just your garden-variety depression, or mid-life crisis, which I had to work through with the aid of counselling and many other helps. It was not a quick process; it took time. But ten years later I wrote another book that changed my life, a book on joy called Champagne for the Soul. From Job to Joy was a long journey, but the difference between the two is just one letter.

The gospel—the good news—is very simple. Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world—including yours. Just believe it.

Next Post: St. John of the Cross & the Dark Night of the Soul