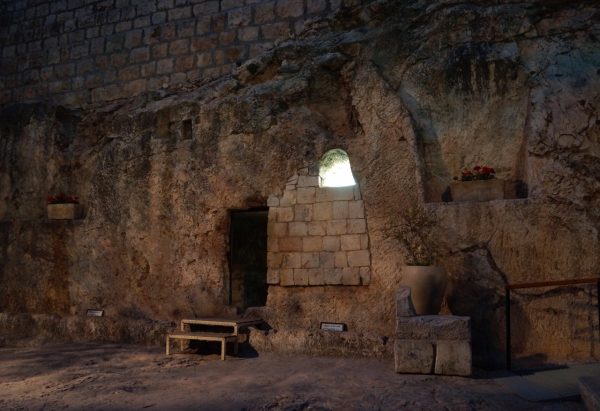

At the place where Jesus was crucified, there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb, in which no one had ever been laid. –John 19:41

Our discussion of the stone relics associated with Easter would not be complete without mentioning the Garden Tomb.

Located outside the present walls of Jerusalem, near the Damascus Gate, this site is treasured by many Protestant Christians as the authentic place of Jesus’ crucifixion, burial, and resurrection. It’s not hard to see why it might be preferred to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The latter is ugly, chaotic, claustrophobic, constantly crowded, and choked with pious bric-a-brac, while the Garden is a beautiful, spacious area full of trees and greenery and peaceful footpaths. Moverover, not far away is a rocky escarpment presumed to be Golgotha, The Place of the Skull, for in the cliff face one really can make out the lineaments of a skull.

Undoubtedly the Garden Tomb gives the modern pilgrim a much better feel for what the original site might have been like. Unfortunately, no archaeological evidence supports its authenticity. Both the design of this tomb and the presence of similar graves nearby prove that it dates not from the first century but from much earlier, as early as the seventh century BC. And scripture states clearly that Jesus’ resting place was “a new tomb.” From marks left by stone-cutters’ tools we know that the Garden Tomb was remodeled in Byzantine times, but there is no sign of first century use.

The site of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, on the other hand, as we saw in an earlier chapter, is supported by much evidence. One counter argument is that it lies inside the present-day walls of Jerusalem, while scripture states that Jesus was crucified “outside the city gate” (Heb 13:12). But there are clear indications that the first century walls followed a different course which did not enclose this area. Modern excavations to a depth of fifty feet below the church, and also just south of it, have revealed that this was once a rocky, uninhabited region used as a quarry—a natural setting for other first-century Jewish tombs that were found here, short tunnels burrowed into the rock face. The quarry strongly suggests, and the presence of tombs proves beyond doubt, that this area would have been outside the city walls of the time, for the Jews did not permit burials (let alone crucifixions) within the city.

Having presented these facts, all I can do is to recount my own experience of these two sites. Without any knowledge of the archeological data, I went to the Holy Land fully expecting that the Garden Tomb was where I would come closest to experiencing the true ambience of the first Easter morning. I’d been prepared for this by friends, and I’d also been warned not to expect much from the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. To my great surprise, my experience was just the opposite. The Garden, while very lovely, left me spiritually cold, while in the outlandish Church, in the midst of a hectic day, I felt filled with a most extraordinary peace—a peace which, remarkably, returned to me as I worked on these last two chapters.

Not proof, certainly. But let me close with a remark from two commentators who tend to be thoroughly skeptical of almost all the other holy sites in Israel: “We think that along with St. Peter’s House in Capernaum, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem is one of the few Christian holy sites with any credibility.”(1)

(1. John Dominic Crossan & Jonathan L. Reed, Excavating Jesus: Beneath the Stones, Behind the Texts, HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2001, p 248.)

Photo by Karen Mason

Next Week: The Primacy of Peter