About the middle of the feast Jesus went up to the temple and began teaching. –Jn 7:14

Near the southwest corner of the Temple Mount, about halfway up the wall, is a curious projection of stones whose purpose remained a mystery for many centuries, until in 1838 an American scholar named Edward Robinson identified it.

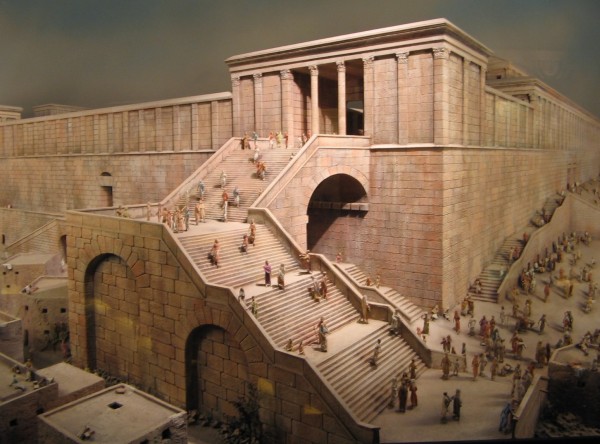

Robinson’s Arch, as it came to be called, turns out to be the anchor for an enormous staircase leading up to a major gate into the Second Temple. All that remains of this Herodian structure is the fifty-foot-long spring (the point at which an arch rises from its support) embedded into the wall. At ground level forty feet in front, excavators found the stump of a large pier, also fifty feet long, built on the bedrock. Between these two anchors would have stretched a flight of stairs, turning a right angle to descend the rest of the way to street level. Among the most massive stone arches of classical antiquity, it spanned a thoroughfare called the Tyropoeon street, twenty-eight feet wide and lined with shops that formed part of the city’s Lower Market.From the spring of the arch down, all the stones in the wall date from the original Herodian construction. The higher courses were added later.

This whole area was excavated after 1967, when twenty-six feet of rubble had to be removed to get down to street level. Before that, Robinson’s Arch sat practically on the ground, so that people could walk up and touch it or even sit on the stringer. Visitors today to the Jerusalem Archeological Park can walk along a good length of the original paving stones of the Tyropoeon street below the arch, between raised curbstones and the remains of entrances to ancient shops. Adjacent to the Western Wall, it is used by some groups as a place of worship. (For a marvelous video tour of Herod’s Temple, see “Virtual Reconstruction of Second Temple Mount.”)

This is an area that Jesus would have frequented. He might have paused here on His way to the Temple to chat with shop owners or passers-by, or been stopped (as He was everywhere) by those seeking healing. Other Temple gates were commonly used by visitors or pilgrims, or for the endless deliveries of animals and wood and other supplies, but this southwestern gate, along with the two southern gates around the corner, were the customary entrances for Jewish worshipers. What is particularly interesting about the gate above Robinson’s Arch is that it opened onto the Royal Portico (or Royal Stoa), a large basilica complex that served commercial and legal functions, somewhat like a Roman forum or Greek agora, so that some viewed it as not properly a part of the sacred Temple precincts. Because King Herod, the Temple’s builder, was not of a priestly family and so could not enter the holy chambers of the Temple itself, the Royal Portico with its magnificent stairway provided a place of suitable majesty for his official visits accompanied by an elaborate entourage.

We can imagine another King, with a humbler retinue, mounting these stairs intent on a purpose more grim. For the Royal Portico is where Jesus cleared away the tables of the moneychangers and stalls for selling birds and animals. The Temple’s commercial circus was so rife with corruption that Jesus had every right to be angry about it. Nor was He the only one: About thirty years later an incensed mob repeated His gesture, sweeping away the whole bazaar. And ten years after that, the entire Temple was gone.

Photo #1 by Mike Mason

Photo #2: Древний Иерусалим, реконструкция. “Reconstruction model of Ancient Jerusalem in Museum of David Castle.” 2005. Wikimedia Commons.

Next Week: The Trumpeting Stone