The last two verses of the Book of Job tell us that after his ordeal, “Job lived 140 years. And so he died, old and full of years.”

Since we do not know what age Job was when his trials began, neither can we say exactly how old he was when he died. If the Septuagint is right in saying that he lived 240 years in all, then he would have been 100 at the outset. This is probably a reasonable estimate (if anything is reasonable when it comes to the ages of the patriarchs). What does seem clear is that Job’s unusual length of years places him in the patriarchal era, probably somewhere in the period between Noah who died at the age of 950 and Abraham who died at 175.

In any event, when Job died he was “full of years,” a Biblical expression signifying not merely longevity but fullness of wisdom and godliness. To be full of years is to have seen everything there is to see and to have done everything there is to do, to the point that now one is so full of it all that there is no room for anything else. There is no room for any more time or any more world; one is crammed to the gills with it. There is room only for eternity and for God. If Job was “blameless and upright” before his ordeal, then think what he must have been like 140 years after it. He must have had so much holiness that his flesh would have been practically crawling with it.

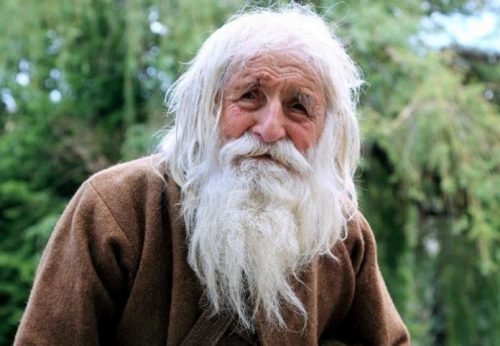

Is that not exactly how it is with old saints? Even their physical bodies seem to take on an aura of sanctity. Their very skin, wrinkled and blotchy as it is, glows translucently, like a great dripping tallow candle lit from the inside. You can see God in the lines of these faces, in the wattles of the neck, in the creases around the eyes and on the mottled hands. These folks are still sinners just like everybody else, and yet one can almost see the sin falling off them. Evil no longer frightens them; they eat it for breakfast. Death does not terrorize; they run swiftly toward it like Olympic youths. Such people have their feet firmly on the ground, and yet they are almost in Heaven. Their bodies are falling apart, but about the persons themselves there is something fantastically young and ageless—one might even say sexy! They are like the very first glistening little shoots of tender green pushing their way up through the mud and the snow on a February day that is both winter and spring at once.

What business do these decrepit, dying old folks have being so brazenly radiant, so totally and profanely themselves, so full of a hair-raising God-awful wildness of pure liberty? Never have their bodies so held them down, and yet never have they come so close to bumping their fool heads on the sky, so lightsome are they. (Why else would they walk around stooped and bent over?)

We young folks, still bound on the wheel of time and worldliness, can barely stand the stench of sanctity around these old saints. It unnerves us. These people are like ancient and unimaginably dangerous gangsters, like Mafia godfathers. Long ago they hung up their sawed-off shotguns, and now their weapons are of an entirely different order; now they transfix you with only their eyes and the gravel in their throats. One sits utterly transparent, X-rayed, in their presence. One has the feeling that they can do literally anything they want and get away with it. Their faith has made them untouchable. The blood of Christ has made them incorruptible. Even as they lie on their beds breathing their last, the mighty power of the resurrection is fairly jumping out of their mouths. Flat on their backs, they are dancing a jig with Jesus. They have linked hands with the Lord and are dancing a tarantella on top of their own graves, and their feet are as nimble and irreverent as the hooves of satyrs. When you go to view their bodies in the church or funeral parlor, if you stand very quietly and listen very closely, you might even be able to hear them singing—singing at the top of their lungs while swinging their steins like shameless beerhall revelers. And then, if you press your ear close against the cool, hollow wood of the coffin, perhaps you will make out the words of their song, for they are the same words sung centuries before by a man named Job: “I know that my Redeemer lives, and that in the end he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been destroyed, yet in my flesh I will see God” (19:25-26).

~an excerpt from The Gospel According to Job, pp 445-6

Next Post: The Image of God: Sovereignty and Racism