(A meditation by Barbara Cawthorne Crafton)

We didn’t even know what moderation was. What it felt like. We didn’t just work: we inhaled our jobs, sucked them in, became them. Stayed late, brought work home—it was never enough, though, no matter how much time we put in.

We didn’t just smoke: we lit up a cigarette, only to realize that we already had one going in the ashtray. We ordered things we didn’t need from the shiny catalogs that came to our houses: we ordered three times as much as we could use, and then we ordered three times as much as our children could use.

We didn’t just eat: we stuffed ourselves. We had gained only three pounds since the previous year, we told ourselves. Three pounds is not a lot. We had gained about that much in each of the twenty-five years since high school. We did not do the math.

We redid living rooms in which the furniture was not worn out. We threw away clothing that was merely out of style. We drank wine when the label on our prescription said it was dangerous to use alcohol while taking this medication. “They always put that on the label,” we told our children when they asked about this. We saw that they were worried. We knew it was because they loved us and needed us. How innocent they were. We hastened to reassure them: “It doesn’t really hurt if you’re careful.”

We felt that it was important to be good to ourselves, and that this meant that it was dangerous to tell ourselves no. About anything, ever. Repression of one’s desires was an unhealthy thing. I work hard, we told ourselves. I deserve a little treat. We treated ourselves every day.

And if it was dangerous for us to want and not have, it was even more so for our children. They must never know what it is to want something and not have it immediately. It will make them bitter, we told ourselves. So we anticipated their needs and desires. We got them both the doll and the bike. If their grades were good, we got them their own telephones.

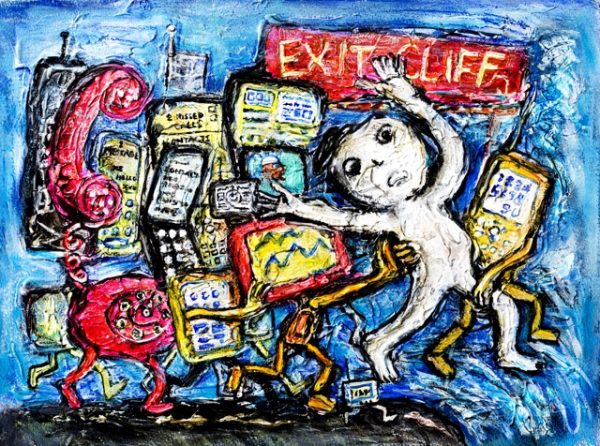

There were times, coming into the house from work or waking early when all was quiet, when we felt uneasy about the sense of entitlement that characterized all our days. When we wondered if fevered overwork and excess of appetite were not two sides of the same coin—or rather, two poles between which we madly slalomed. Probably yes, we decided at these times. Suddenly we saw it all clearly: I am driven by my creatures—my schedule, my work, my possessions, my hungers. I do not drive them; they drive me. Probably yes. Certainly yes. This is how it is. We arose and did twenty sit-ups. The next day the moment had passed; we did none.

After moments like that, we were awash in self-contempt. You are weak. Self-indulgent. You are spineless about work and about everything else. You set no limits. You will become ineffective. We bridled at that last bit, drew ourselves up to our full heights, insisted defensively on our competence, on the respect we were due because of all our hard work. We looked for others whose lives were similarly overstuffed; we found them. “This is just the way it is,” we said to one another on the train, in the restaurant. “This is modern life. Maybe some people have time to measure things out by teaspoonfuls.” Our voices dripped contempt for those people who had such time. We felt oddly defensive, though no one had accused us of anything. But not me. Not anyone who has a life. I have a life. I work hard. I play hard.

When did the collision between our appetites and the needs of our souls happen? Was there a heart attack? Did we get laid off from work, one of the thousands certified as extraneous? Did a beloved child become a bored stranger, a marriage fall silent and cold? Or, by some exquisite working of God’s grace, did we just find the courage to look the truth in the eye and, for once, not blink? How did we come to know that we were dying a slow and unacknowledged death? And that the only way back to life was to set all our packages down and begin again, carrying with us only what we really needed?

We travail. We are heavy laden. Refresh us, O homeless, jobless, possession-less Savior. You came naked, and naked you go. And so it is for us. So it is for all of us.

~from Barbara Cawthorne Crafton, “Living Lent,” in Living Lent: Meditations for These Forty Days, Morehouse Publishing, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1998.

Next Post: Binding Arbitration

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.info/sv/join?ref=GJY4VW8W

I am an investor of gate io, I have consulted a lot of information, I hope to upgrade my investment strategy with a new model. Your article creation ideas have given me a lot of inspiration, but I still have some doubts. I wonder if you can help me? Thanks.

oh I love this and I want to do so much more than love it…I want it to change me. I want to be changed. I have been making trips to the Goodwill….cleaning out what is more than I can use..and yet there is more and more….I want all kinds of “things” but the most crucial is a nod from God which is what cuts to the heart as He has given me both His nod & His life and why is it not enough? Today I surrender my will, my way. I acknowledge that I live out my faith as if it is a test and I am failing. I tell things He already knows and fear in my silences I am in denial of some enormous truth. It’s hard to tell the truth & not come off sounding like a victim. Just for today (what’s left of it) I will keep my focus on Christ and choose Trust. Thank you for this post