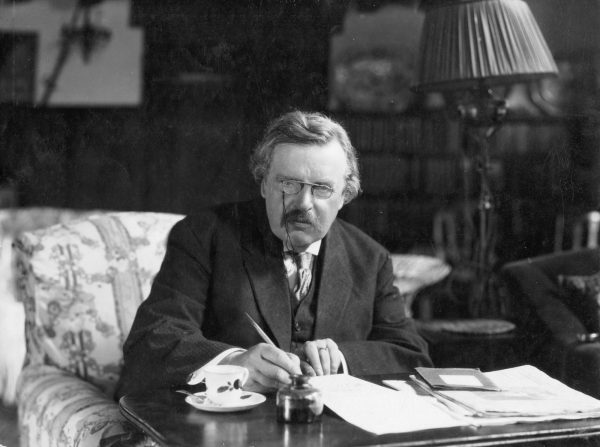

Dale Ahlquist has written an excellent one-volume introduction to G.K. Chesterton called The Apostle of Common Sense. Here’s just an excerpt on GKC as prophet:

Again and again G.K. Chesterton revealed a foresight that can only be described as prophetic. Though he died three years before the beginning of World War II, he warned against Hitler before anyone else. He warned that there would be an outbreak of violence against the Jews. He accurately predicted that the war would come, that it would begin on the Polish border, and that it would be the most horrible war in history. Long before that, he saw that the airplane would totally change warfare, leading to war conducted not just against soldiers but innocent civilians. He recognized that technology, which is always advertised as being for our betterment, can just as easily be used to improve ways of killing people.

He said that as an industrial society we would use electricity, water power, oil, and so on, to reduce the work imposed on each of us to a minimum. But the machine would become our master. And technology would create as many problems as it solved:

The same modern industrial civilisation, which aims at rapidity, also produces congestion.

The modern world is a crowd of very rapid-racing cars all brought to a standstill and stuck in a block of traffic.

Civilization has run on ahead of the soul of man and is producing faster than he can think and give thanks.

Chesterton predicted both the rise and the fall of communism in Russia. He predicted that, in the meantime, the government there would be a rigid bureaucracy, that small nations would be swallowed by that empire, but would break loose again and survive the empire.

And while the fears of the Western world would all focus on the godless communists in Russia, Chesterton warned that the next great heresy would be right here, and it would be an attack on morality, especially sexual morality. He said:

The madness of tomorrow is not in Moscow but much more in Manhattan.

He correctly predicted that there would be “a fashionable fatalism founded on Freud”. He said we would at once “exalt lust and forbid fertility”. We would eventually be no different from the commercial centers of antiquity, like Carthage, where they threw their babies into the fire. He predicted that abortion would be considered a sign of “progress”. He said that “our materialistic masters would put birth control into an immediate practical program” before anyone was even aware that it had happened, and that it would be “applied to everybody and imposed by nobody.”

“The old parental authority”, he said, would be swept away. Its place would be taken, “not by liberty or even licence, but by the far more sweeping and destructive authority of the State”. The State would become the only absolute in morals, so there would be “no appeal from it to God or man, to Christendom or conscience, to the individual or the family or the fellowship of all mankind”. We would then to try to use the government to remedy “the failures of all the families, all the nurseries, all the schools, all the workshops, all the secondary institutions that once had some authority of their own”. There would be rebellion, but the new rebels would not lay down rules, only exceptions. And Chesterton said the one institution that he was sure would expand is the institution we call prison.

Chesterton seemed to be writing for today when he said that the Christian was expected to praise every creed except his own. He said that extremism is a fashionable term of reproach and any Christian who actually wanted to argue on behalf of his own faith is dismissed as an “extremist”.

The great Catholic apologist Frank Sheed, whose wife, Maisie Ward, wrote a biography of Chesterton, was one of many who marveled at the uncanny precision of Chesterton’s predictions. And he said of Chesterton, “When a man is as right as that in his forecasts, there is some reason to think he may be right in his premises.”

~from Dale Ahlquist, G.K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense, Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 2003, pp 173-7. (References to all the above quotes will be found in the text.)

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

I have read your article carefully and I agree with you very much. This has provided a great help for my thesis writing, and I will seriously improve it. However, I don’t know much about a certain place. Can you help me?

(usbdfv)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(tsnsrz)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(uiczpf)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(lijodj)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(gwqmen)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(ymjjbm)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(lvubfr)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(ejvdxs)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(sbrqqy)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(uwptnj)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(ziwuja)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

(heyhdj)Not a bad article, by the way a lot from – costaricarealestate.info

Great prediction for the days to come in our generation…..