As we approach December it’s time for a reminder of my book 21 Candles: Stories for Christmas. Here’s one of those stories, which a friend liked so much that he read it to his family every Christmas Day for over three decades. Read on …

Many centuries ago there lived a man who devoted his life to roaming the earth in search of all its most magnificent works of architecture. He had been to Rome, to Athens, and to other great ancient cities, and he had even journeyed to the Orient (something unheard of in his day) to view its splendid temples and palaces. Wherever there was rumored to be a grand or unusual edifice, there the traveler bent his footsteps.

Many centuries ago there lived a man who devoted his life to roaming the earth in search of all its most magnificent works of architecture. He had been to Rome, to Athens, and to other great ancient cities, and he had even journeyed to the Orient (something unheard of in his day) to view its splendid temples and palaces. Wherever there was rumored to be a grand or unusual edifice, there the traveler bent his footsteps.

Born into a family of builders, and independently wealthy, at first the man had intended to travel only for a few years, with the idea of steeping himself in the design and construction techniques of a wide variety of cultures. But everywhere he went he heard stories about new wonders that lay just beyond: a fabled citadel on a mountaintop, a golden pagoda at the end of a certain road, or an entire city of green marble on the other side of a sea. He found such tales irresistible, and wanderlust drew him ever onward.

Like most travelers, it was not only that the new and the unknown tugged at him—it was that the old and familiar pushed him away. And disillusionment, once surrendered to, has a way of furring the eyes like cataracts, until one day a man may wake up to discover that whatever he looks at, new or old, gives more pain than pleasure.

It was in just such a world-weary state that the traveler found himself one winter, late in life, while sojourning in a Mediterranean land. Jaded with grand spectacles, he had come to settle in a single humble room in the one inn of a small village, where he determined to stay put for a while and try to unravel the riddle of his life. For the thought came to him hauntingly—now that his own porticoes were sagging, his own columns and foundations giving way—that a human might by nature be not only a traveler, but himself a building, his every beam and stone stamped with an unquenchable yearning for permanence.

One afternoon, while sitting in the village square by the well, he chanced to fall into conversation with a peasant who was drawing water there for his sheep. As always with strangers, the traveler began to give a glowing report of his adventures, talking easily and enthusiastically about all the exotic places he had seen. (After all, if one could no longer experience real joy and wonder in life, the next best thing was to talk as though one did.)

“Well, well,” nodded the peasant, having listened attentively to the whole account. “It sounds as if you’ve seen just about everything there is to see in the whole world. And I suppose you’ve taken in our local attractions too, have you?”

“Oh, yes—to be sure!” chuckled the traveler, catching the joke. “I’m afraid you haven’t much to boast of around here.”

“Ah, but on the contrary,” responded the peasant in apparent earnest. “Have you not seen our Royal Palace? It’s right here in the village, and I can assure you there isn’t anything to match it in all the earth. If it’s grand buildings you’re after, then this is the thing to see.”

Scratching his head, the traveler looked around at the collection of homely boxes that made up the tiny village, and at the empty rolling hills beyond. Was the old fellow daft? There was certainly no palace here. Even the largest building in sight, the inn where the traveler himself lodged, was a mean and unimaginative structure.

Seeing his bewilderment, the peasant beckoned with his staff and said, “Come, let me show you. It would be a shame to journey as far as you have and to miss seeing the greatest attraction of all.”

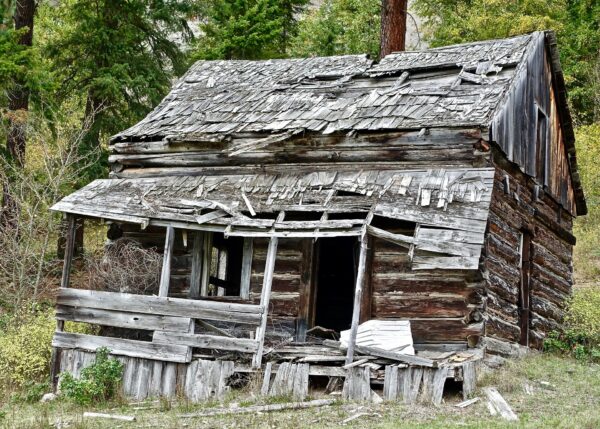

So with that, driving the sheep ahead of them, the two old men set off together through the winding laneways until they reached the outskirts of the village. There they halted, as the guide gestured toward a clump of ramshackle outbuildings behind a row of abandoned tenements.

“There,” he announced with curious finality. “There is our Royal Palace.”

The traveler rubbed his eyes. Was he looking in the wrong place? But no—his new friend was pointing, unmistakably, to what appeared to be the very last and least of all the buildings in the village. Apart from a few rock doves flying in and out of crannies in the walls, the structure looked uninhabitable, unfit even for livestock. And beyond lay nothing but fields of stubble rising up to the desolate hills. Only the wind seemed at home here, moaning and sighing with that eerie sound it reserves for deserted places.

The traveler, uncertain now what manner of man he might be dealing with, remarked cautiously, “It doesn’t look like much from here.”

“You’re right,” responded his guide. “From here you wouldn’t know it from a hole in the ground. But what you’re actually seeing is just the facade of the Royal Palace. To view the Palace itself, you must go inside.”

Accordingly, the two men went forward until they were standing beneath the sloped roof of a most precarious-looking lean-to. Sunlight filtered in dusty curtains through loose boards, and the straw scattered about the earthen floor was dirty and mildewed. In one gloomy back corner a door was visible, hanging askew from a single hinge. Apparently it led into a stable.

“I’ll have to be about my business,” advised the peasant. “But you just go on ahead and have a look around. Right through that doorway you’ll find an anteroom. Wait there, and after a while you’ll be attended to.”

“Attended to?” inquired the surprised traveler.

But already the old man was gathering his sheep and herding them off along a narrow path that wound through the grain fields up toward the barren hills.

“I’ll return for you shortly!” he called back merrily with a wave of his crook, and soon the other was left all alone with the doves, the moldy straw, the cool quiet shadows and curtains of dusty light, and the piping wind that crept ghostily through the rafters with an almost-human sound.

Well—what did he have to lose? Stepping gingerly toward the back corner and swinging open the door, the visitor entered into the darker interior of what looked to be a cowshed. Here, a single pencil-shaft of sunlight lanced through a crack in the very apex of the roof onto the earthen floor. The traveler stood still, blinking, peering into the shadows.

What in the world was he doing here? Allowing himself to be hoodwinked by an old prankster? Perhaps it was a fitting conclusion to a lifetime of futile wanderings.

As his eyes adjusted to the dimness, the first thing he noticed was an unusual knothole on the farthest wall. Perfectly circular and curiously bright, it was haloed by a distinct sunburst pattern in the surrounding wood. Drawing nearer, he saw that the old planks held other intriguing designs, and the longer he studied these the more fascinating they grew. Indeed, hidden amidst the swirls and ridges of the wood grain were shapes of ferns, trees, birds, and animals, so that all in all the effect was like that of a large mural. Suddenly the odd thought came to him that the scene might portray the original forest from which these very boards had been cut! Not only that, but before he quite realized what was happening, the flat surface of the wall seemed to recede and to take on three-dimensional depth, until all at once he felt himself to be standing, incredibly, in the sun-shot reality of a Mediterranean forest of cedar, fir, oak, with a cloud of brilliant songbirds threading the lacework of boughs. And there, not twenty yards off, stood a small antelope gazing at him with eyes as solemn as an angel’s.

Recalling with a start that, as perfectly real as this looked, it could not be so, the amazed visitor took a step back. But immediately his attention was drawn to a second wall, where once again the flat surface melted away beneath the swirling image-rich patterns of the wood grain—until now the vista that unfolded was that of a great mountain with a majestic waterfall leaping from its heights into a valley decked in the luminous gold and crimson robes of autumn. The whole scene was more vibrant and gorgeous than the grandest of Byzantine mosaics.

“My word!” exclaimed the traveler. “What remarkable work!” For it struck him that such breathtaking dioramas could not possibly be attributed to chance designs in old boards, but only to the consummate artistry of some master craftsman. And all the more admirable it was for having been so cunningly concealed.

The observer was not given long to reflect, however, as he was distracted by a sound—a familiar, tremendous roar that encompassed him as completely as if he were hearing his mother’s heartbeat in the womb. Turning toward the third wall, he discovered himself on a long sandy beach with thunderous combers higher than himself breaking, dissolving, bowing to the shore and then washing glassily right up to his sandaled feet. And all at once he felt it—the cool, curling water laving his soles! For some time he stood there, lost in wonder, letting the waves carry all his thoughts away.

Finally, however, it was the fourth wall that displayed the most marvelous tableau of all. For here, as the visitor glanced back at the rude doorway through which he had entered, in a twinkling he was transported bodily back to the wooded hills and valleys of his own birthplace. Once more he stood high upon a favorite lookout, his native city spread out below garbed in the sapphire sash of its shining river, which seemed to lead toward the ends of the earth. And once more he felt, as he had so often as a boy, the thrill of the wide world spilled at his feet like treasure and just waiting to be explored. So full of poignancy and nostalgia was this scene, so charged with the shimmering magic of childhood, that it moved him to tears, and he hung his head as the memories flooded in.

Even as he cast down his eyes, the very straw on which he stood was transformed into field upon field of golden wheat tossing in the wind, while in another direction appeared chains of lakes with turquoise waters through which rainbow-colored fish glided like jeweled shadows. And elsewhere the humble dirt floor gave way to spectacular canyons and gorges or to flower-filled meadows or broad plains alive with game.

As if all this were not enough, when at last the observer lifted his eyes overhead to where the one ray of light traversed a chink in the peak of the roof, he was surprised to see that this was not a beam of sunlight, but a star, dazzling in its splendor! And off among the darker slopes and rafters shone the full moon, the planets, and all the heavenly host, unfurled to infinity upon the imponderable velvet of deep space.

Overwhelmed with awe, he fell to his knees and bowed his face into the musty straw. Never in all his travels had he beheld such stupendous artwork, so perfectly realistic, so rich with grandeur. How was it possible?

At that moment, the stocky frame of his peasant friend appeared behind him, his raised shepherd’s crook forming the silhouette of a question mark in the doorway. Turning toward him, the visitor implored, “Tell me, I beg you—what place is this? And who, pray tell, is the Master Builder of this grand Royal Palace?”

“Why, friend,” replied the shepherd, “don’t you know? You are in Bethlehem, and this is the Royal Palace of Christ the King. But listen: What you have seen so far is only the Anteroom of the Palace, and I assure you, it is nothing compared to the Throne Room! Come, won’t you follow me and meet the King Himself?”

Next Post: The Phenomenon of the Ubiquitous Christmas Store