I hope I live long enough to see the next generation of electric shavers. Indeed I wonder if there has ever been a new generation of this appliance, since the ones today don’t work much better than the one my dad loaned me for my first shave back in the 1960’s.

I now have a recent Braun model, Series 7, complete with an elaborate ‘Clean & Renew’ system that is very satisfying to use. But when it comes to actually trying to shave, I have to drag this machine repeatedly and with considerable effort across my face, especially over stubborn patches, in order to convince it to produce an effect resembling smoothness. Even then, the result falls far short of what can be achieved manually with a blade.

Shaving, it seems, is one of those activities that may never be satisfactorily automated. Similarly, will they ever invent a machine capable of stuffing a pillowcase? Such homely, mundane tasks are too complex for machines, too personal. Ordinariness, it turns out, does not necessarily equate with simplicity. On the contrary, the ability of the everyday world to captivate, to keep us interested throughout a long lifetime, is due partly to its inherent complexity. To say that if you’ve seen one daffodil, one cloud, one drop of water, you’ve seen them all, is simply not true. The simplest elements of our world have the capacity, if we attend to them, to provide endless intrigue, whether for the scientist, the mystic, or the janitor enjoying his backyard of a summer’s evening.

Whole books have been written about the most basic everyday objects. Consider The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance by Henry Petroski. After citing an exhaustive list of essential supplies that Henry David Thoreau wrote before his twelve-day excursion into the Maine woods, Petroski notes that the writer failed to mention a pencil: “Perhaps the very object with which he may have been drafting his list was too close to him, too familiar a part of his own everyday outfit, too integral a part of his livelihood, too common a thing for him to think to mention.”

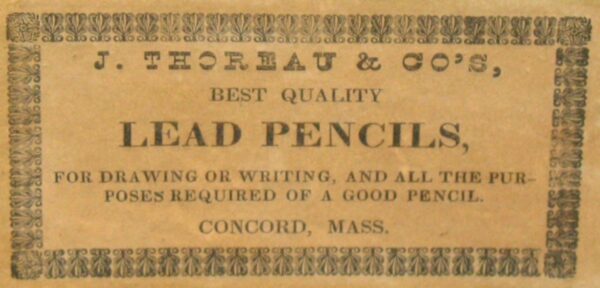

This is especially ironic considering that Thoreau came from a family of pencil makers. As Robert Sullivan writes in The Thoreau You Don’t Know, after burning out as a writer in New York in his post-collegiate years, Thoreau returned home to work part time in Thoreau and Company, his family’s pencil firm, whose products were “the best-known pencils in the United States, praised by artists and artisans.” Surprisingly, Thoreau turned out to be “an excellent pencil maker” who introduced some significant innovations. For example, whereas previously a pencil had to be cut in half to be filled with lead, Thoreau invented a means of injecting the lead directly into a hollow wooden shaft.

In the final analysis it may be impossible to say whether the mind is more satisfied by complexity or simplicity, for in the most mundane objects the two qualities converge. Perhaps the attraction of everyday things is how they tease us out of rational thought, shifting us into another mode of perception. Only the quotidian has the power to slow our minds enough to restore our grasp on plain reality. As the poet Wallace Stevens put it, “The worst of all things is not to live in a physical world.”

Next Post: And That Is What We Are: Embracing the Child