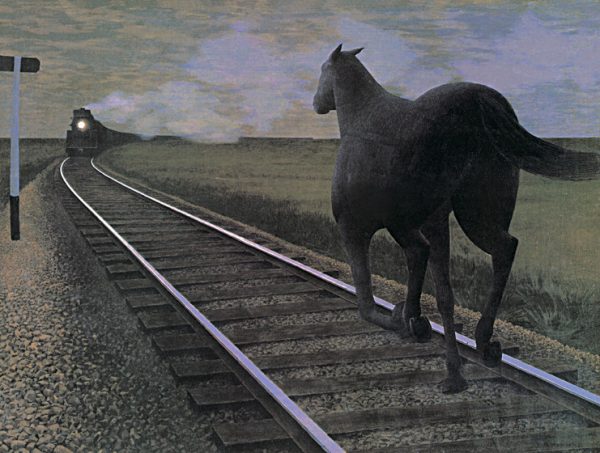

Alex Colville’s art is full of black animals: dogs, cats, crows, horses. Consider his most famous painting, “Horse and Train.”

Note the word order of the title: Just as the dog obscured the priest in “Dog and Priest” (see last week’s post), in this picture the horse, far larger than the train, dominates.

This horse is big and black and is loping down the tracks. Immediately the realistic illusion is interrupted by a modernist mystery: Why is a riderless horse cantering straight toward an oncoming train? One answer: Because the horse (or its invisible rider?) is bent on forcing a confrontation with the human world and its technology. (Another of Colville’s paintings portrays the black, riderless horse from John F. Kennedy’s funeral cortège, prancing before a white church.)

Who will win this encounter between horse and train? Common sense says that a speeding train will destroy a horse. But that is not what the painting says. On the contrary, the painting suggests an entirely unexpected, irrational outcome.

Look closely at the train: Is it really speeding? To my eye, it seems almost hesitant, as if slowing down. Its steam is an enigmatic violet, color of the unconscious. Perhaps it is beginning to wonder: Who is this who is rushing so purposefully toward me? Even the curve of the tracks (viewed from the train’s perspective) suggests a question mark. The horse, by contrast, has a strong aura of purpose. It is focused, quietly determined, relentless. This is a ‘dark horse’—an expression that describes a competitor about whom little is known but who comes out of nowhere to be victorious. In fact Colville’s original title for this work was “A Dark Horse Against an Armored Train,” a line borrowed from a poem by Roy Campbell:

Against a regiment I oppose a brain

and a dark horse against an armored train.

In short, my money is on the horse to win. For this is no ordinary horse; it is an angelic, apocalyptic horse.

Colville’s animals play a role similar to that of angels in earlier art: They are warners, watchers, witnesses, messengers. No chubby, comfy cherubs, these; they are holy ones. Colville himself remarked, “Part of my fascination with animals is that I think of them as incapable of evil. For me, a cat, cow, or dog is really like an angel in a certain way. My admiration for animals is unconditional.”

Now look back at the dog in “Dog and Priest.” Unlike the horse, he seems worried. Very worried. He is seeing something, or aware of something, that the man is not. At the deepest level, this dog is a realist. He senses what is at stake in human life, and he desires not only to guard the priest but to warn him, to wake him up. The relaxed priest gazes out upon a scene that he probably sees as calm, when actually the water and the sky appear as troubled as the dog does. Nature is trying to communicate with this man through its angelic messengers, but the man is oblivious.

In this age of both widespread crisis and numbed indifference, Alex Colville gives us new eyes with which to see the dark horse loping toward us down the tracks.

(First published in Crisis Magazine, Oct 30, 2015)

Next Post: I Asked for Wonder: Abraham Joshua Heschel