The Canadian painter Alex Colville (1920-2013) was that most curious of artistic hybrids, both a realist and a modernist. In fact art critic Jeffrey Myers, in an article entitled “Dangerously Real,” called Colville “one of the greatest modern realist painters.”

Colville’s paintings reproduce ordinary objects, people, scenes—indeed the more ordinary, the better—with near-photographic realism. Each of his works took months to produce, with layer upon layer of thinned paint painstakingly applied dot by dot to a primed wooden panel, and the opaque surface finally sealed with transparent lacquer—all with the purpose of depicting reality.

But what kind of reality? That of surface appearances? Here is where Colville’s modernism comes in. With deceptively simple means, his art draws us far beyond the surface into much deeper waters. Beneath the ordinary veneer, always something odd, sombre, or ominous lurks, suggesting loneliness, isolation, anxiety, even violence or doom. Thus his use of realistic content has little to do with naturalism; more than just reflecting reality, he parses it, producing pictorial parables, or what he himself called “myths of mundanity.”

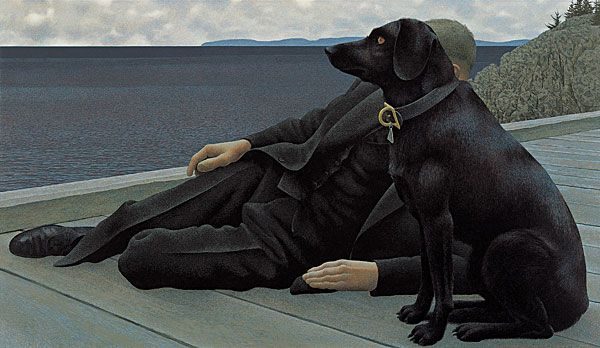

Consider the painting “Dog and Priest.” The figure of the man is in a relaxed pose and the water appears relatively calm; at first glance this may seem but a quiet, reflective interlude. But wait: The man’s face is completely obscured by a troubled-looking black dog with overly-red eyes. We know the man is a priest from the painting’s title, but we might also guess this from his black clerical suit. His priest’s collar, however, is invisible, hidden (humorously) by the dog’s collar. (In fact a priest’s collar is known colloquially as a “dog collar.”) Moreover the two collars together form the shape of a cross.

What is going on here? It may help to know that Colville believed that people are evil by nature but that animals are innocent, and that animals accordingly can have the effect of protecting and purifying us. Add to this the fact that a dog is a symbol of faithfulness. In this painting the dog seems actively on guard, watching out for the priest, even absorbing his anxiety so that the man can enjoy a few tranquil moments. By entitling the painting “Dog and Priest” (note the word order) Colville invites the question, “Which is which?” The two figures are so similarly garbed as to suggest that the dog may be serving as priest to the man.

This is a far cry from the sort of Christianity that believes animals have no souls and will not gain entrance to heaven. We know that there are trees in heaven—why wouldn’t there be animals? Are there really no fish in the River of Life? Indeed “wherever the river flows swams of living creatures will live and there will be multitudes of fish” (Ez 47:9). Again, if the kingdom of heaven is devoid of animals, how is it possible that “the wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat” (Is 11:6)? And what are we to make of the fact that the beings closest to God’s throne are neither humans nor angels but four “living creatures”? As Psalm 84:3 puts it:

Even the sparrow has found a home,

and the swallow a nest for herself,

where she may have her young—

a place near Your altar,

O Lord Almighty, my King and my God.

In Colville’s painting, without the presence of the dog with his collar there would be no cross, no evidence of sanctifying grace. Indeed the two bodies of the man and the dog produce the shape of a triangle—perhaps hinting at the Trinity? Or if not the Trinity, they certainly suggest a shared unity and stability. Thanks to Fido, these two of God’s creatures will be saved (if at all) together.

(First published in Crisis Magazine, Oct 30, 2015)

Next Post: Horse and Train: How a Photorealist Portrays Angels (The Art of Alex Colville, Part 2)